Improvisation & Experimentation

The beauty of not knowing

Of all the approaches to art that we may take, experimentation is probably the most conducive to true expression. Experimentation is free, unrestrained by concept or preconception, and ideally expressive of something beyond our own limited viewpoint. Experimentation opens the door to chance, to accident and to unexpected inspiration.

It is the royal road to new ideas.

Changing fixed parameters to remove limitations

There are many fixed assumptions and forgone conclusions in our creative practice, even though we may have never thought of them. We may inadvertently follow prescribed paths and take cultural norms as gospel. But if we become aware of these factors we can choose to dismantle or ignore them, and open ourselves up to whole new vistas of possibility. This can be as simple as radically altering the tempo at which you work, or creating music with no bass at all, or with no beats. A good example is tuning: in the West, for most of the last 300 years we have been breaking up the octave into 12 equal intervals. If this tuning system is replaced with another, an entirely different range of tonal colour appears. This is why many foreign musics sound so different to our Western ears. Another example might be that you should never play a harp through a guitar pedal, or play a violin with a small rubber mallet (although that’s perhaps a better norm to follow).

Extended techniques

This is the name given to the use of non-standard playing techniques on an instrument. As in the example above, it fulfils the purpose of breaking old habits and prescribed modes of being, but also has the benefit of opening up huge new ranges of timbre and expression. There is no limit to the range of possibilities here, which is what makes it such fertile ground for experimentation. The increase in novel technologies also opens up an ever wider range of playing possibilities, with electronics expanding the scope of new tones ever further, although extended techniques probably go back much further than conventional wisdom supposes. A violinist friend, on me asking about the potential for extended techniques, informed me that Paganini had explored the use of items being placed under the strings and other novel ideas 200 years ago. A famous recent example is the prepared piano, attributed to John Cage, where individual strings within the piano are treated with a range of additional items such as coins, rubbers or paper, thus creating a range of novel timbres. However, there are many examples in contemporary music; these include adding metal objects under the strings of a guitar, blowing through a brass instrument without using the mouthpiece, and using the amplified key clicks on a clarinet.

photo credit: Siyao Li

Creation of sound sources & instruments

A further step in the same direction quickly takes one to developing new sound sources and instruments from scratch. This is very fertile ground for creativity, as the whole basis of sound is up for grabs, and the limitations are entirely self-imposed. There is probably a limit to the range of things which make a interesting sound, but that limit is not easily reached, and subtle alterations in a single approach can have widely varying sonic characteristics. Pre-existing approaches such as strings and bells can be complimented by washing machine drums, sticks, rubber sheets or whatever else is lying to hand. These creations can also have an artistic expression of their own, with the possibility of applying an aesthetic sensibility to their design. Natural forms and materials or highly technical machines are two wildly different possibilities, and any combination of elements in between. My first creation was an extremely simple monochord, utilising a single low cello string on a metre length of oak, amplified by a contact mic, and played with a bow. I initially created it to solve the problem of not always having a cello handy to play at the shows I was writing music for. The incredible thing about it was that it created the most beautiful harmonics when played, despite its simplicity, and could be folded in half and packed in a backpack for travel. From there I have progressed to making zithers and bell arrays, and using automation and simple robotics to enhance the playing potential.

Use of the voice

The voice is an instrument most of us have access to, and the one most directly linked to our subconscious mind. It is the ideal tool for improvisation and experimentation, capable of an incredible range of tones and inflection, and intimately linked to our inner modes of expression. The voice has the added benefit of having a hard-wired receptivity in the consciousness of the listener, our brains being adapted to prioritise vocal information. Whether used for percussive, noisy or melodic elements, the voice will nearly always draw a listener’s attention. Ideas created using the voice can later be developed for other instruments, or incorporated as they are, harmonised or expanded. The voice is free to use, always at hand and highly expressive; the perfect tool for experimentation. These days there are also a huge range of processing options available, from converting sung parts to MIDI control information to AI voice-swapping.

Adopt a stance

A great way to open up new inner avenues of expression is to adopt a stance, or to create in an imagined style. By playing a certain role, one can suddenly inhabit a new consciousness, and express ideas in a way that you never would in your normal mode of operation. For example, “play in the style of Bach” or “play like a jazz drummer” open up totally new modes of approach, and may produce a result that you could never have imagined. Ultimately it’s about play.

Artificial Limitations

“Necessity is the mother of invention” as they say, and the creation of limitations can have a stimulating effect on the way we view a project. An excess of possibilities, or a tendency to adopt a path of least resistance, can both hamper the creative act in different ways. The creation of limitations short-circuits these issues and gives the brain a dilemma to deal with, a problem to solve. This activates new arenas of thought and stimulates creativity.

A simple example that I use as a matter of course is to limit the number of tracks I am going to use, or to limit the types of instruments. But it can be used in much more creative ways too, such as only using the voice for all the sounds in a piece, or only allowing sounds recorded in the garden. Earlier I referred to artificial limits, and this is one enforced habit that has helped me break some tendencies towards busy-ness. Limiting oneself to five tracks, or to three instruments, can help us to make the most of what we have without resorting to yet another part to add interest or to keep the flow going. We are forced to be ingenious. Another recent self-imposed limitation has been not to use artificial effects in live performance compositions, instead relying solely on acoustic sources and amplification.

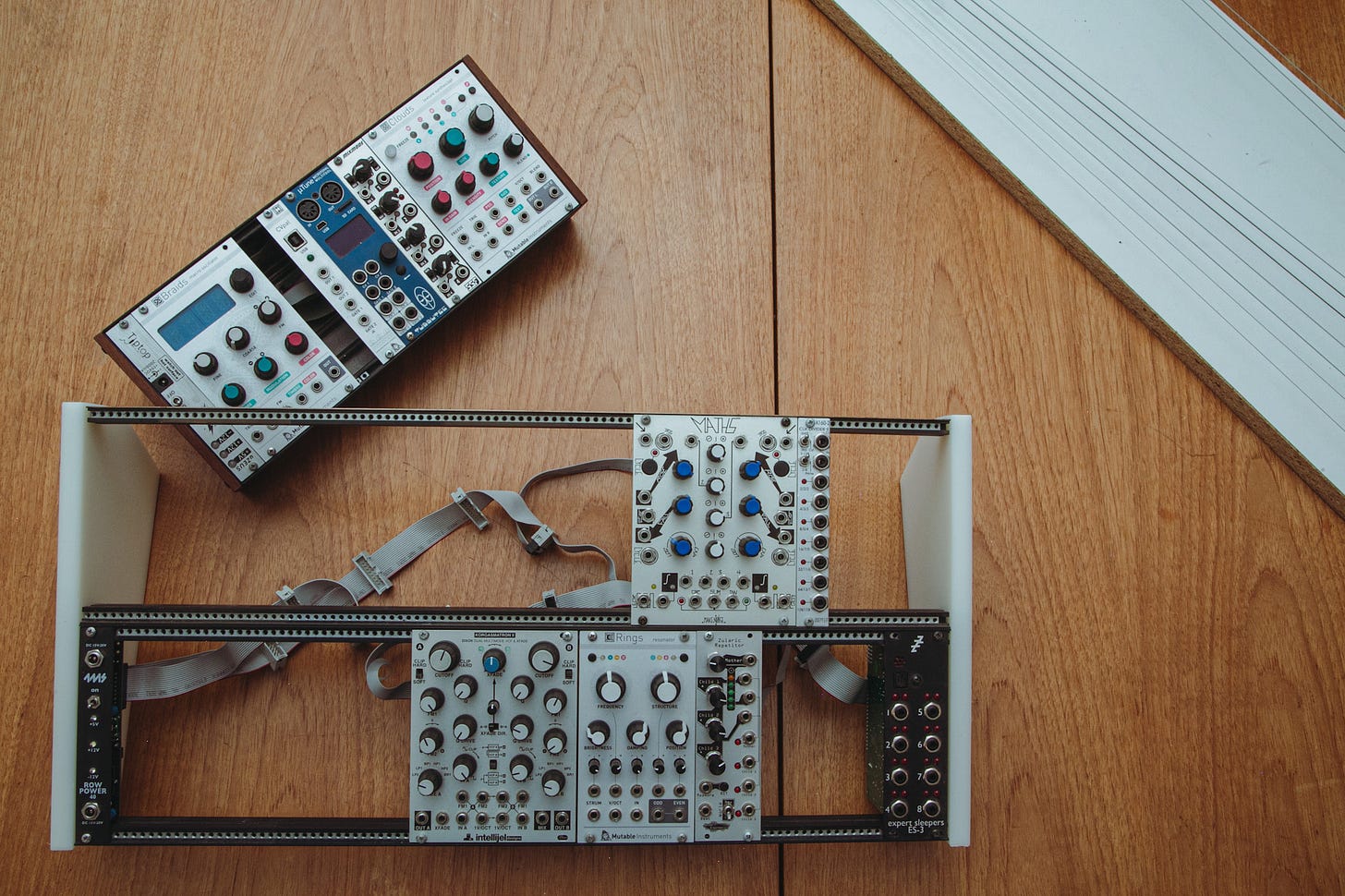

Modular synths and complex instruments

Some instruments are so complicated that by their very nature they encourage experimentation. If the range of possible options is so great that you cannot possibly contain them in a logical thought process, then you may as well hit “record” and just play about. Over time, of course, you begin to develop shorthand tricks and techniques with an instrument, the experimentation giving way to certain possibilities that produce better results than others. But with a modular synth you can simply rewire the modules you have, or insert a new one, and you are once again in new territory, with new potentials and more to learn. By not allowing the brain to become comfortable in a fixed arena of possibilities, you constantly challenge it to re-think and remain playful in the moment. The same is true for software and hardware instruments, but with each having their own respective strengths; hardware has the advantage of tactile control, and the possibility of quickly altering multiple parameters at once, whilst software has an open-ended supply of potential new connections and often access to strange parameters hidden beyond reach of a hardware synth. For me this is also true of the Kyma software, or Cycling 74’s Max if that’s your boggle.

Background technique expands the range of possibilities

Experimenting is all very well, but even here technique and acquired skills play a large part. The experimental possibilities open to a violinist who is the master of their instrument, and a beginner who has been using Ableton Live for 2 weeks, are clearly going to be widely divergent. The more time that is spent in the pursuit of new sounds and technique, the more that the motor skills and ears will ‘tune into’ their roles and become subtle and expressive agents of creation. There is however an advantage for the beginner who has ‘beginner’s mind’; an open-minded approach to the possibilities offered by an instrument or software without the lifetime of conditioning in a particular direction. In our example above, the violinist might approach a new string instrument in a way much more akin to the way they approach their lifelong instrument of choice, whereas the non-specialist is far more likely to see possibilities outside the box, perhaps treating it as a percussive instrument or blowing over the strings.

FURTHER READING:

Alvin Lucier – Experimental Music 109

Stephen Nachmanovitch – Free Play: Improvisations in Life & Art