Creating Instruments

Why make instruments?

One of the things that changed most for me in the last few years was becoming an associate artist with Cryptic in Glasgow, an Arts organisation that specialises in audio-visual and multimedia art and performance. Finally, I had an outlet for musical works which fall outside the standard parameters of composition or music for release. For me this can include writing for acoustic instruments, performances for particular spaces, and usually a mixture of acoustic and electronic sources. I also realised that I might further push the parameters of acoustic sound by fashioning my own instruments, and thus create the timbres and tunings that I am aiming for.

In software I was used to having access to a near-endless array of controls to create the necessary sounds, but with acoustic instruments this is more challenging. There is no question that forward thinking modern ensembles such as the London Sinfonietta or London Contemporary Orchestra have been exploring the further reaches of what’s possible with acoustic instruments for years, and that both composers and players are increasingly aware of experimental electronic music that has influenced the push towards new timbres and forms. However, working with trained orchestral musicians on experimental ideas has its challenges, either from the perspective of having enough time to experiment with ideas, or from the potential clash of cultures which might make communicating these ideas difficult. By making one’s own instruments, it is possible to hone the techniques that produce the best results, whilst also having time to modify the sound-creation device itself. It opens up a huge new vista of potential ideas.

Methods of approach

As I explored the idea of creating my own instruments, I realised that this was nothing new of course; many composers have explored the idea of creating or modifying instruments to suit their purposes and their compositions. This is especially true of the composers of this century, from John Cage’s prepared piano, to Harry Partch’s multitude of eccentric instruments, and the more experimental fringes of the avant-garde. There is also a thriving scene of instrument makers, building and inventing new approaches to sound, often utilising new technologies and novel materials, and often documenting their work in books and online. For my own part, I was drawn to purely acoustic sources, but with the electronic augmentation of contact microphones and player-mechanisms. This is really a practical concession on my part; the microphones allow the instrument to interact with the electronic world of my software, whilst the player mechanisms allow me to accompany myself without having to use a looper, or perform parts for which I don’t have the technical skill (yet!).

That’s the thing about creating a new instrument; you don’t yet have a fixed way to play it. There is an organic development of instrument and technique as you get to know its limitations and idiosyncrasies. Having said that, there are very few instruments which don’t have some shared heritage with an existing form, and musicians with some existing ability on another instrument are no doubt at a great advantage in playing any new one. A harpist will no doubt find a home-made zither to be fairly comfortable ground, and the breath and mouth control of a trombonist will be equally useful blowing a hosepipe carnyx. I grew up playing the cello and drums so I have naturally been predominantly drawn to strings, and percussion instruments are also appealing for their lower technical requirements, both for building and for playing. I will document the creation process for the 4 bridge zither built for ‘Creation’ in another post.

The chime bar created for Etanan by Florence To

Constituent parts

Once you break down the constituent parts of a sound-producing instrument, further approaches become available. One needs a sound source, which must be made to vibrate or resonate in order to make sound (sound IS movement ultimately, which is why nearly every creation myth includes sound). This then usually needs to be amplified with either a resonant body, as in the case of a cello or guitar, or with electronics such as contact mics. The body further modifies the sound with overtones and other resonant qualities, depending on the materials and size, so this in itself is a vital part of designing the instrument’s sound. Instruments that are well known have tended to adopt a small number of approaches to such questions, with wood being the predominant resonant body material for both string and wind instruments. However there is nothing stopping us from using metal as the resonant body, or glass, or any other material that resonates. For example, a string attached to a cymbal will produce a sound combining the timbres of both, and a glass pipe organ will sound different to one that uses metal pipes. There are many new options open to us.

The materials used can also take on an expanded role, incorporating an added layer of meaning into an instrument or composition. Harry Partch made his famous ‘cloud chamber bowls’ from Pyrex vessels used in the study of sub-atomic particles in the 40s, and Pedro Reyes has constructed a multitude of string, wind and percussion instruments from gun parts confiscated from the Mexican cartels. Materials from nature, waste materials from our society, materials with a history or interesting context can provide an artist with a whole raft of connections and inferences. My neighbour is an artist who uses litter to create a huge array of interesting and beautiful instruments. And then there are the other artistic decisions that can weave meaning into a construction; the shape, the number of strings or bells, the colour, the decoration. All of these factors together go towards creating an instrument and an object of meaning. If it sounds good too, then all the better.

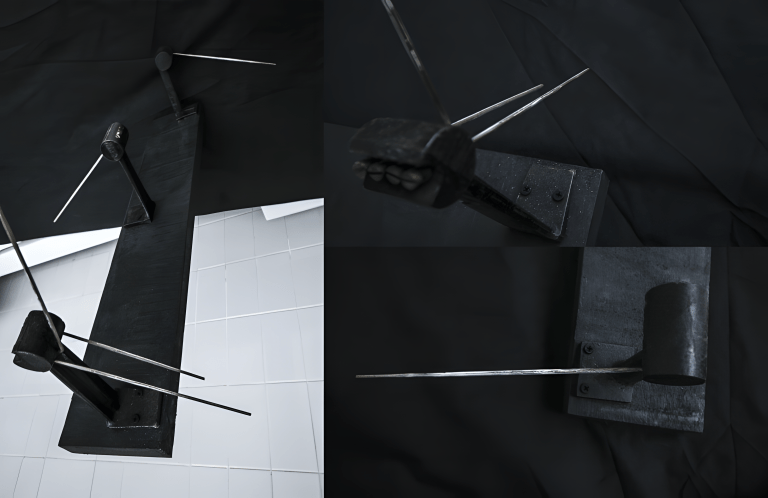

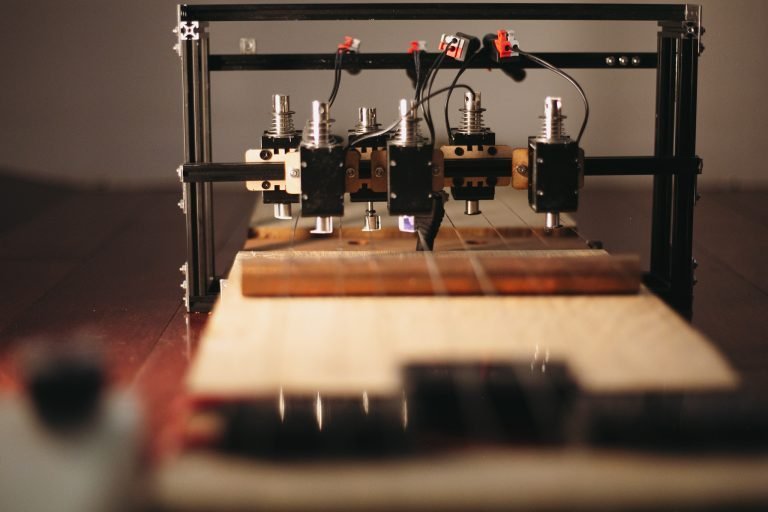

The player mechanism for Creation’s four bridge zither

I also think it’s worth saying something here about the technical aspects of any electronic elements that can go hand in hand with building an acoustic instrument. Building a player mechanism for example can add a layer of sophistication and practicality. There are a range of possibilities here; player mechanisms can be designed to accurately play MIDI notes fed to them using more complex arrays of solenoids or robotic mechanisms. Or they can use rotating gears that can only play fixed melodies, or more random systems that play parts within certain constraints. For my own ‘Creation’ zither, I utilised both an accurate MIDI solenoid array, and a more random rotating wheel plectrum that only had a speed control (see the separate post on the making of that instrument). There are many people out there experimenting with Raspberry Pi and other Arduino systems to control various aspects of instrument design, and I’d particularly point people in the direction of VulpInstruments and Hackaday for ideas in this line. Microphones are the other obvious electronic addition, and contact mics can be bought for just a few pounds/dollars. Contact mics are very simple devices that record sound via the vibrations transmitted through a material, rather than through air, so they are ideal for these kind of projects. They pick up no feedback from speakers and can be placed in any number of places to pick up unusual aspects of an instrument’s sound, such as under a player mechanism or directly on a string. For my monochord, created for So Below, the mic is attached directly to the string, wedged between the string and the wood of the instrument, to pick up the full range of overtones.

Factors in Making an Instrument

- An instrument is an extension of the composition process in every way. The instrument may exist purely for the sake of the demands of a particular composition.

- The instrument can (and does) direct and lead the style and focus of a composition.

- Consider new combinations of forms eg: wind and string/mallet and rock/marble and singing bowl

- Prototyping – There are many ways to go about trying out ideas. This includes things such as Makerbeam/CNC/laser cutting, as well as the more traditional forms such as woodwork.

- Consider the differences between different strings/resonant bodies etc, and experiment to find out what works best in any particular instance. I found huge variations between different types of strings, for example.

- Player mechanisms – many approaches are possible – rotational, longitudinal, robotic, digital

- Electro acoustic elements – eg: motors/contact mics

- Encouraging of improvisation – no one knows how your instrument is played so there is a whole load of exploration involved in how to play it.

- Use of symbolism in construction – eg: number of strings/ aesthetic design of instrument.

- Examples: Harry Bertoia / John Cage / Harry Partch / Bart Hopkin

Some Useful Resources

Alvin Lucier – Music 109 – Notes on Experimental Music – An excellent overview of much of the experimental avantgarde of the 60s and 70s, from the perspective of someone who was not only in amongst it creating music of his own, but also then communicating those ideas to students. As a result this is a great balance of artistry and practical information.

Bart Hopkin – Musical Instrument Design – Bart Hopkin is the man responsible for the most in-depth and useful guides to instrument making in print, at least when we’re talking about the more experimental end of things. His designs cover everything from strings, winds and bowls to sticks, rattles, brass, shells etc etc. His website at barthopkin.com includes a back catalogue of his creations and is full of inspiration.

The Instruments of Harry Partch – Harry Partch is one of the great originals of the American avant garde. He created a wealth of new instruments and was highly influential in his use of new tuning systems and alternative scales. Some instruments have become famous, such as the ‘cloud chamber bowls’ but there is much to learn from all of his creations.

Vulpestruments – This is the website of Tom Fox and includes loads of good technical info on working with instruments and electronics. This is where I found out about the DADA Automat that I use for triggering purposes. But there is also a wealth of information on strings, pins and everything else in making your own instruments. Again, this is a man who works in education, so the information is in a very digestible format. Very useful.

Guthman Musical Instrument Competition – I actually just discovered this, but it will be a useful resource moving forward. It is the site of an annual instrument design competition and is a rich resource for new thinking in instrument making. It’s not about nicking others’ ideas, but more to do with expanding your thinking on what is possible and the approaches available.